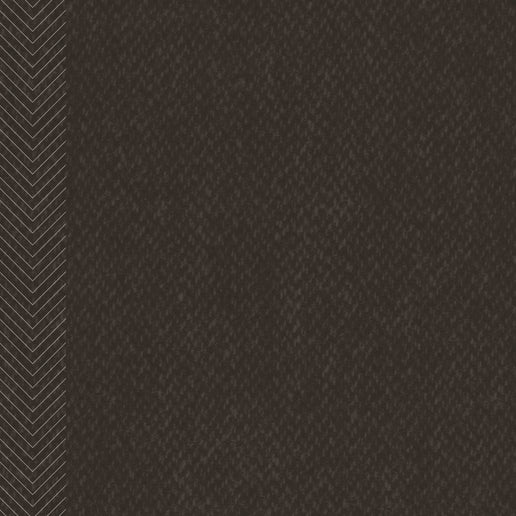

IF there is one yarn colour that encapsulates the magic of the Harris Tweed blending process it is, ironically, black.

Technically it is a ‘non-colour’. But never mind that. Fashion and design absolutely loves black. From Henry Ford telling a customer the Model T was “available in any colour - as long as it’s black” to Audrey Hepburn immortalising the little black dress in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, there has never been another ‘colour’ to touch it.

Until, that is, Harris Tweed Hebrides created Paris Black.

Very much a limited edition, this was an exclusive colour blend created for one of the company's international customers. Even the name is appropriate, with Paris Black playing homage to the city of chic and its citizens such as Madame Coco Chanel, who famously adored black, declaring it “has it all”.

What makes Harris Tweed’s Paris Black so wonderful is that it has all the power, presence and panache of true black while containing the tiniest trace of a handful of bright colours (purple, blue, green and red), to make it sing.

This is an exceptionally chic black but that is only because its colours are so beautifully balanced due to the great care taken at the blending stage.

The blending part of the Harris Tweed process - along with the other mill-based processes of dyeing, spinning and finishing - is protected and guaranteed by the Harris Tweed Act 1993 just as much as the famous weaving itself.

Harris Tweed Hebrides has nearly 150 different coloured yarns and only four of these are solid colours. All the others are blended colours, which gives Harris Tweed its instantly recognisable ‘flecked’ look.

Some will only contain two colours, such as black and white, while others comprise as many as nine.

Every recipe for a coloured yarn will stipulate what percentage of coloured wool (dyeings) are to be used. These recipes are followed by the mill workers literally taking ‘handfuls of this and handfuls of that’ - in the right order to ensure that even a small amount of colour will be evenly mixed throughout a larger colour batch.

The exact percentages of colours are, of course, a closely guarded secret and getting them right is usually the result of hours of painstaking work by designer Ken Kennedy.

When he is working on creating a yarn colour, Ken will work with minute pieces of dyeings, teasing and blending them together with his paddle brushes. Powered by elbow grease, the brushes open up the fibres and then blend them together into a mixed coloured ball resembling, in miniature, the hue and shade of a final blended yarn.

The paddles themselves are pretty low tech. They are, in fact, pet brushes bought for Ken by his daughter Kelly (who also works at the mill) as he was struggling to use his proper - but heavy and unwieldy - hand-carding paddles.

The quantities involved in trying out a colour blend are tiny, with each dyeing weighing as little as a tenth of a gram. The result, a sample ball of blended colour, may weigh only a couple of ounces but once Ken is satisfied with the colour, the mill workers swing into action to produce a full batch of up to 1000lb.

After assembling all the dyeings needed for a particular colour recipe, the mill workers follow that mix recipe by taking the right number of handfuls of wool from each sack and dropping it on top of a special hatch in the floor.

A blend that is to be 95 per cent of one colour and five per cent of another would, for example, simply be 95 handfuls of the first colour followed by five handfuls of the second, with the process repeated until all the wool has been piled up.

Then the hatch opens and the machinery whirrs into action, with the huge blending machine sucking in all the wool and blending it together by blowing it around. The result is a glorious organised chaos, that looks something like this:

This process is repeated, to ensure thorough blending, and the wool then sprayed with oil and water in order to lubricate it for spinning and hand-weaving.

After the blending, the multi-coloured piles of clumped wool are sucked through the pipework to the giant cupboards at the back of the carding machines where they await the next stage of the production process.

Here, they will be transformed from random clumps of wool into neat ‘spools’ of carded wool ready to be spun into a single ply yarn of workable strength. In any colour (just as long as it’s black...)!